This reminiscence was included in the book Henri Huet: J’etais Photographe de Guerre au Vietnam by Horst Faas and Hélène Gédouin. Published in French in 2006, the book includes a collection of photographs by Huet, one of four news photographers killed when their helicopter was shot down over Laos on February 10, 1971–49 years ago.

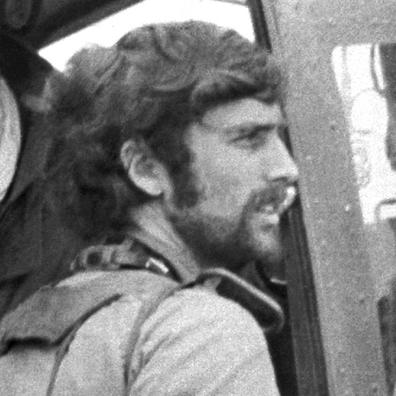

By Michael Putzel

© 2006 All Rights Reserved

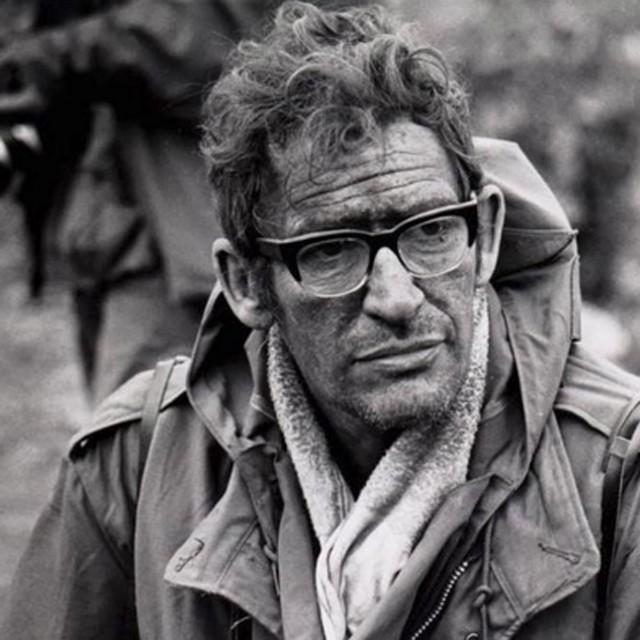

I went looking for Henri to give him a message. It was February 10, 1971, in the mountainous northwestern corner of what was then South Vietnam. We were both covering the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese invasion of Laos to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail, but we had been with separate units when the operation kicked off, and we hadn’t seen each other in a couple of days. I liked working with Henri when I got the chance. He had a quiet, gentle streak that instilled confidence in those of us more than a decade younger with only a fraction of his experience covering combat. In our world, he was legend, but he didn’t lord it over us.

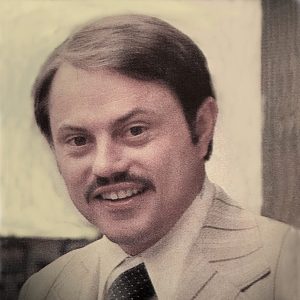

photo by Michael Putzel

After dawn, I hitched a ride aboard the first Army helicopter I could find flying out to Khe Sanh, the just re-opened combat base in the mountains where U.S. and South Vietnamese forces had set up their forward headquarters. The weather was chilly—even cold for the tropics—and the gray sky drained the color from the hilly jungle. I found Henri on high ground near the South Vietnamese “TOC,” the sandbag-fortified tactical operations center where he and several other photographers had been told they would be in the first group of journalists permitted to witness the offensive inside Laos. It wasn’t Henri’s kind of assignment; he preferred going out with small combat units, where the interaction was more personal and where he so often captured the faces of war. This group was to accompany the operation’s commanding general and his top staff, a “press trip” less likely to encounter actual combat or produce dramatic photos. But up until then, no news photographers or correspondents had been permitted to cross the border, and Henri liked to be first.

The night before I had managed to get a phone call through to the AP’s Saigon bureau, and the photo desk told me that if I saw Henri I should remind him his South Vietnamese visa was about to expire and that he should return to Saigon to take care of it. The bureaucracy required all foreign journalists to renew their visas every three months, and to do that, we had to leave the country, apply for a new visa at a consulate abroad and wait about a week to get back into the country. It was a nuisance—but also an opportunity to take a few days off from the war. Most of us looked forward to the chance for some rest, good food and the conveniences of a modern capital anywhere but Vietnam. I told Henri I’d take his seat on the chopper and cover for both news and photos in order for him to return to take care of his paperwork. It was a futile gesture. He wasn’t about to abandon one of the biggest military operations of the war to fly home to tend to some technicality. He looked at me and smiled, the crow’s feet by his eyes crinkling, lending his smile a familiar warmth. We both knew the bureaucrats would give him and the AP trouble if he overstayed his visa, but problems like that eventually got resolved, perhaps with the help of a couple cartons of American cigarettes or a few rolls of Kodak film. Henri was determined to keep his seat, and we parted before the flight took off. I left him outside the headquarters below the helicopter landing zone, standing around with the other photographers who were planning to go on the mission. I headed back to the U.S. side of the base to do some reporting on the progress of the operation.

A couple hours later, I was walking past an American unit’s makeshift temporary headquarters and overheard a voice on a radio saying in English through heavy static something about “helicopters down.” That was enough to alert me to trouble, but I didn’t know at first that it involved Henri. An officer emerged from the sandbagged bunker and gave me another tidbit. Two Huey helicopters apparently had been shot down. It wasn’t immediately clear whether they were U.S. or South Vietnamese, but in the course of the next few minutes I was able to gather enough information to be horrified at the prospect that I had lost my friends. I was a reporter working the story, but I also remember a pit in my stomach, a rushing anxiety—and a sense of urgency to tell the AP what I knew. There was no way to call Saigon from Khe Sanh; there weren’t any phones. I had to get back to Camp Red Devil, a U.S. base about 25 miles away that had better communications and was serving as a press center for the journalists covering the Laos operation. By the time I found a helicopter going that way and persuaded its pilot to take me, I knew I was carrying terrible news. The details came later. An American chopper pilot and cavalry troop commander, Major Jim Newman, and his co-pilot had watched helplessly from a distance as a string of olive drab Huey helicopters flew, apparently lost, over a known and charted North Vietnamese antiaircraft gun position a few miles inside Laos. The skilled gunners on the ground below fired on the first and third choppers in the string. Henri and his companions were aboard the first aircraft, which took a direct hit, exploded in flames and fell a few thousand feet in a fireball, smashing into a mountainside. Newman later flew me over the crash site surreptitiously to show me no one could have survived the shoot-down.

“Red Devil, get me MAC-V!” “MAC-V, get me Tiger!” Fighting the phone system in Vietnam was part of a correspondent’s life. We had to know the relay points, claim military priorities we probably weren’t entitled to and shout like soldiers to be heard over the waves of static that drowned our voices. It could take hours, and then the connection might be lost in a moment. When the bureau answered 500 miles to the south, I bellowed for Richard Pyle, the chief of bureau. He picked up the phone, and I started to dictate, slowly and clearly. I had no idea how long the connection would last.

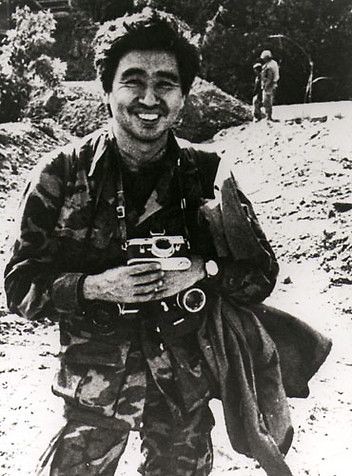

“A VNAF helicopter…has been shot down in Laos…. All aboard are missing and feared dead…. They include…four civilian news photographers. They are…Henri Huet of AP….” Pyle, a consummate professional, choked in horror as he pounded the keys of his aging typewriter, then barked for silence in the office to enable him to capture every word. I gave the other names: Larry Burrows of Life magazine, Kent Potter of United Press International, Keisaburo Shimamoto of Newsweek. One other photographer, Sergeant Tu Vu of the South Vietnamese army, was also aboard. He had aspired to shoot for the AP if he ever got out of the army and sometimes slipped me rolls of film that he shot on operations no Westerners got to see. Two senior South Vietnamese officers and a four-man flight crew went down with them. I didn’t know at the time that one of the officers was carrying the plans and communications codes for the whole operation, a potentially devastating loss if the documents fell into the hands of the North Vietnamese.

I told Pyle everything I had learned about the crash, still a sketchy report that left many questions unanswered. Then I went in search of colleagues from the other news organizations that had people on the flight. At the military briefing for the press that afternoon, a local version of what were known in Saigon as the “Five O’Clock Follies,” I asked an officer for a few minutes to tell my fellow correspondents what we knew of the crash that had claimed Henri and the others. By that time we knew they weren’t coming back.

Henri had stowed his gear, a rucksack with some spare fatigues and a shaving kit, in a bunkroom known as a “hootch” that had been set aside as sleeping quarters for the press. There were no cameras or valuables; he had all his photo equipment with him. I collected what was left behind and made arrangements for someone to carry it back to the bureau in Saigon. For some reason, Henri had not taken his “boonie hat,” a floppy, wide-brimmed military cap he frequently wore in the field. He had stuck a flêchette, an inch-long, sharpened blue steel dart, in the cotton hatband for decoration. Flêchettes, since banned, were packed in artillery shells and fired only at point-blank range when a unit was about to be overrun. They testified to close-quarter combat. I kept the hat and wore it in Henri’s memory until it blew off my head into the sea from a sailboat in February 1974, almost three years to the day after his death.