Blog

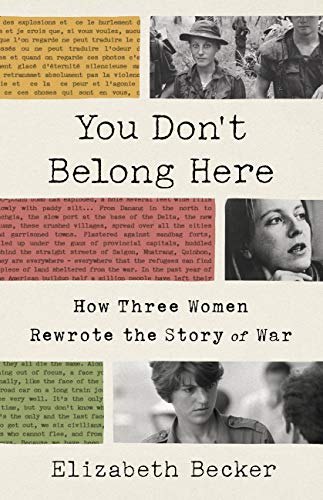

“You Don’t Belong Here”

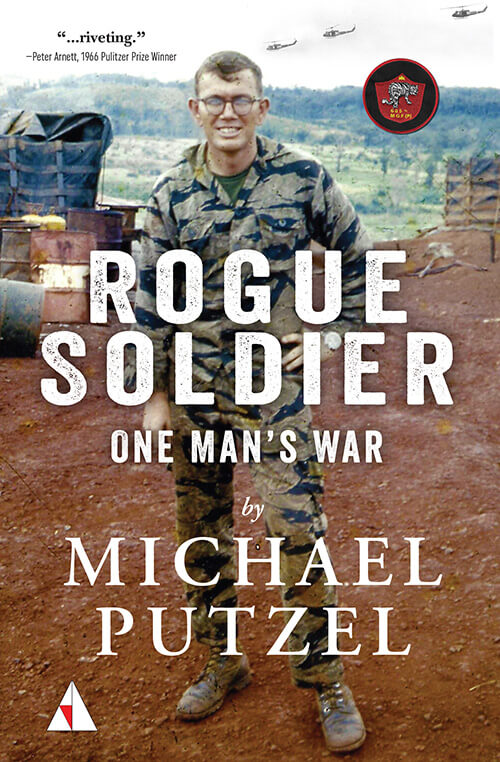

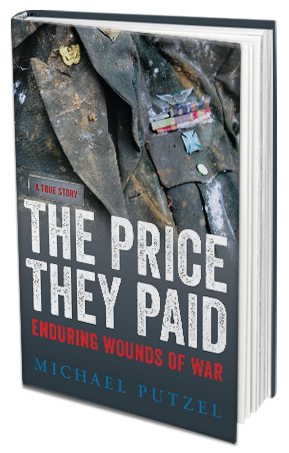

Posted by Michael Putzel • March 22, 2021

I spent 2 1/2 years covering the war in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, and I am astonished how little I knew about the female photojournalists and correspondents who got there before I did.

It may not be so unusual to drop into a big story ignorant of some who had already left. I had read books about Vietnam and the French colonization of Indochina long before I got there, and I knew several of the legendary journalists who were still there when I arrived in 1969.

But French photographer Catherine Leroy and American writer Frances FitzGerald had been and gone by then and weren’t often talked about in our circles. I knew only Kate Webb, the third of the three women whose lives and work are the subject of Elizabeth Becker’s new book: You Don’t Belong Here; How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War.

I worked for The Associated Press that had the largest and much-respected bureau in Saigon, the capital of what was then South Vietnam. Webb worked for our arch rival, United Press International, the smaller, scrappier news service that battled us for every headline it could. We often grumbled and sometimes complained loudly if UPI beat us on a story or photo, but Webb was respected by everyone I knew for her dedication to the story, for pursuing it into the field and for trying to tell it right.

Becker makes the point that all three women paid for their own one-way tickets to the war because no one would hire them to go, and that the three distinguished themselves but were largely forgotten in the four decades since. The author is out to gain them the recognition she says they earned but didn’t receive because it was a men’s world. And it was not just the all-male military command and war fighters they went there to portray, but their own male colleagues who ignored or actively disparaged them because they were women.

The three were not the only women to cover the war, of course, and others have been recognized. Dickey Chappell, the first to fall, was an American photographer who had covered World War II and conflicts around the world. She was killed in Vietnam in 1965, before the others arrived. But Becker decided, “Leroy, FitzGerald and Webb were the three pioneers who changed how the story of war was told. They were outsiders–excluded by nature from the confines of male journalism, with all its presumptions and easy jingoism–who saw war differently and wrote about it in wholly new ways.”

Leroy, a headstrong, difficult personality by any measure, arrived in Vietnam just as President Lyndon Johnson began pouring hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops into the war effort to shore up corrupted and ineffective South Vietnamese forces that followed the French in attempting to ward off a nationalist, communist insurgency. She did not yet speak good English or have much experience with the cameras she carried, yet Leroy managed to win over the soldiers she accompanied into the jungle and, often, their commanders, who could have denied her the access she had to have to show what war was. An experienced parachutist before Vietnam, she made her mark early on as the sole civilian photographer permitted to jump with the 173rd Airborne Brigade in what turned out to be the only parachute-borne offensive of the war. Her dramatic photos, some taken as she plummeted toward earth with the troops, gave her exposure and credibility that could not be denied by disappointed colleagues. A year later, in an even more impressive scoop, she snuck into the besieged city of Hue during the Tet Offensive in February 1968 and was captured by North Vietnamese troops trying to hold the city as U.S. Marines battled to reclaim it for the South. She and a fellow French journalist were released, crossed over into territory controlled by the Marines and returned to Saigon with the first film of North Vietnamese troops in combat. Days later, she went back to Hue and covered the continuing battle, photographing the war with the Marines as they rooted out the enemy.

FitzGerald, a child of privilege with excellent access to her CIA father’s overseas underlings and family contacts in the magazine world, went off to find the Vietnamese villagers and peasants at the crux of what was at its heart a civil war. She found stories and understanding that, according to Becker, were of little interest to the foreign press corps following the action. Her enterprise established her as a serious writer, and after she returned to the United States, she wrote Fire in the Lake, a book about the people and culture of Vietnam that won a nonfiction trifecta: a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award and the Bancroft Prize for history. No book about Vietnam has matched that.

Webb, a New Zealand-born Australian, landed a job at UPI not long after she arrived in Saigon in 1967 and quickly established herself as a worthy field correspondent who followed the troops across flooded rice paddies and into jungles to hear their stories and recount them to readers around the world. She smoked and drank with the rest of them, but her voice was so soft that anyone who wanted to hear had to be silent and listen intently. At a time when news crews were being slaughtered on the roads of Cambodia because no one knew where the front was, she was captured by North Vietnamese soldiers on Highway 4 south of Phnom Penh and was unheard from for three weeks. Her obituaries had been written and widely circulated when she and two colleagues turned up in Phnom Penh 23 days later, having been released by her captors without explanation. I covered the news conference she submitted to a bit later in the day and resented every click of a camera shutter for drowning out her voice as she described the long marches through jungle on bleeding feet and persistent interrogations with the fear of summary execution never far off. She spoke so matter-of-factly of the ordeal that she could have been describing an afternoon at the beach.

All three women returned to cover the war’s final days. FitzGerald was permitted into the bomb-battered North Vietnamese capital of Hanoi as the bold, last offensive kicked off. UPI refused to let Webb go to Cambodia or Vietnam, but sent her to watch refugees from the wars arriving in the Philippines. At the very end, she was flown out to the USS Blue Ridge in the South China Sea to witness the last American and South Vietnamese evacuees arrive by helicopter and touch down on the command ship of a 40-vessel armada that took in the final wave of 900 Americans and more than 5,000 South Vietnamese who were fortunate enough to escape from Saigon. Leroy passed up evacuation and captured the scene as a North Vietnamese tank knocked down the gate to the presidential palace. She accompanied the victors and photographed the official surrender.

There is a fourth character who appears several times in the book as well: Becker herself, who arrived in Southeast Asia in 1973, after the others but, like them, without a job, and stayed on in Cambodia as a reporter for The Washington Post and others for nearly three years as the U.S.-backed regime lost territory, region by region, until the capital of Phnom Penh was surrounded by Khmer Rouge insurgents. The conquerers finally seized control only days before the fall of Vietnam and went on a rampage that will be remembered as one of the greatest human atrocities of the century. Becker continued to write about Cambodia and returned in 1978 with Richard Dudman of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and Malcolm Caldwell, a British professor, for an officially managed tour of the devastated country. They were granted an unprecedented interview by Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge leader, and that night they were attacked in their guesthouse by Cambodian killers who threatened the two journalists and murdered Caldwell. She left the next day and returned once again in 2015 as an expert witness at the international tribunal that convicted two senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge of crimes against humanity. This is her second book about the war.

7 thoughts on ““You Don’t Belong Here””

Comments are closed.

Michael, I truly enjoyed reading your article! I am planning on reading this book as well as Fire in the Lake! The part on the Khmer Rouge, was that referred to as “The Killing Fields?”

Yes, Gary. Various estimates put the death toll at 1.5 to 2 million people killed by the Khmer Rouge before the Vietnamese invaded and overthrew the Pol Pot regime. Countless people were killed by every means available, including starvation.

Bravo Zulu, Mike!

Mike: a very good read. Well done.

Eliot Brenner

Ex Unipresser

Thanks, Eliot. Coming from you, I take it as high praise indeed.

Mike …

Terrific job.

Ron Cohen

25 years with UPI.

Ron,

I’m almost embarrassed by the praise from such able adversaries of long ago. I thank you nonetheless.

Allbest,

MP