Blog

Vietnam Chopper Pilots’ New Chief

Posted by • August 25, 2015

When Clyde Romero is inaugurated as president of the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association on August 29, two members of a tiny Band of Brothers will be on hand to applaud their long-ago comrade-in-arms.

The fourth flying soldier in their practically unique group died a hermit several years ago. All four men were black and members of the same storied air cavalry unit in Vietnam.

At the reunion banquet in Washington of the 16,000-member Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association, retired Colonel Romero will become the first African-American to be elected president of the VHPA.

Romero was 19 when he flew his OH-6 scout into the most dangerous antiaircraft battle ever endured by helicopters and their crews. His “little bird” was part of a flying U.S. armada supporting thousands of South Vietnamese ground forces in an audacious attempt to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, the North Vietnamese communists’ most critical supply line to the south.

With him in C Troop, 2/17th Air Cavalry, a unit of the 101st Airborne Division, were two Cobra gunship pilots and a flight-trained maintenance officer, all of them African-Americans. They were warrant officers promoted from the enlisted ranks in the Army’s haste to train crews for Vietnam, whose jungled mountains and swampy deltas made it ideal territory to fight the first “helicopter war.”

The attempt to cut the trail in early 1971 was a military disaster that crippled some of South Vietnam’s best fighting units and cost the Americans more helicopter crews and helicopters than any battle ever fought.

Except for the “Tuskegee Airmen,” the famed but segregated fighter pilots of World War II, nearly all aviators in the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines were—and still are–white.

“We were a band of brothers,” Romero said, describing a photo of four smiling young black men together at their base in Phu Bai, South Vietnam. Their troop very likely was the only unit of its size in Vietnam with four black pilots. The ranks of military pilots have remained stubbornly Caucasian to this day.

The military newspaper Stars and Stripes reported in 2003 that African-Americans made up 13 percent of the U.S. population, 20 percent of its military, but barely 2 percent of its Navy and Air Force pilots.

Retired Army Colonel Palmer Sullins Jr. of New Orleans, longtime president of the Black Pilots of America, said the percentage of minority pilots in the military has actually declined in recent years since the armed services stopped many recruiting programs and started cutting their numbers as U.S. combat operations tapered off in Iraq and Afghanistan. Sullins, who also flew helicopters in Vietnam, now heads the Friends of Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site in New Orleans.

Almost as surprising as their service together in Vietnam, three of the four—Romero, Eldridge Johnson of Little Rock, Ark., and Robert Farris of Yadon, Pa.—left the Army after their tours in Vietnam, joined the Air Force, became fixed-wing pilots, retired from the Air Force and piloted commercial airliners for major carriers. They have kept in touch with each other for four decades.

The fourth person in the photo, James Casher, was shot down and wounded in Laos but was rescued, recovered from his wounds and returned to his unit, where he earned a Silver Star, the nation’s third highest award for combat valor. His colleagues thought he planned to go to medical school when he finished his military service, but as often happened, they lost touch with him after they left Vietnam.

Casher never got to medical school. He slipped further and further out of touch with family and friends and, thanks to the Internet, was finally located in August 2006 by those who flew with him in Vietnam. He was living in a one-room shack in the woods in Washington state, surrounded by about a dozen mongrel dogs. It wasn’t until after his death a couple years later that neighbors learned he had once been a war hero.

6 thoughts on “Vietnam Chopper Pilots’ New Chief”

Comments are closed.

I didn’t know about this part of Clyde’s military experience beyond that he became an air force pilot. He was flying for USAir when he visited us here. Clyde’s visit with us was a major factor in my coming to terms with Will’s death. Several years ago, I had another connection that’s worthy of Guideposts’ ‘His Mysterious Ways.’ As a result of a local pilot accidentally sitting at the table with some of Will’s friends from his first tour of duty in 1967-68, I was able to go to a reunion and meet men who had flown gunships with him. That was a final piece of the puzzle for me as far as finding peace.

I knew all of these men and the thought that they were black didn’t enter the equation. It was whether or not they were worth a damn in combat and if they had your six. Race irrelevant in combat.

Bob, I completely agree with you, of course. It is a credit to the Condors that in my dozens of interviews for the chapter about Jim Casher, no one from C Troop ever mentioned his race to me. BTW, do you remember the AP story I wrote about you from Khe Sanh?

Michael…

It gives me great pleasure just to say I know you and the people of which you speak. We thank the Good

Lord for delivering such a huge talent to weave our

stories, at least the ones worth telling…God Bless

and many tanks…

Jim Kane (21)

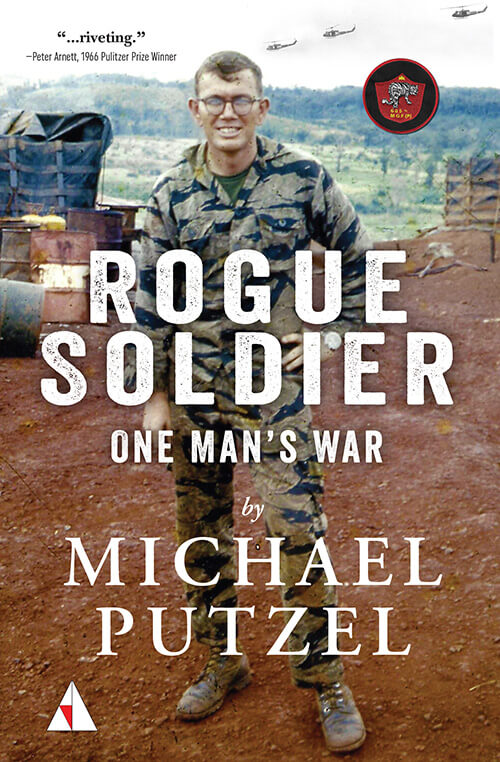

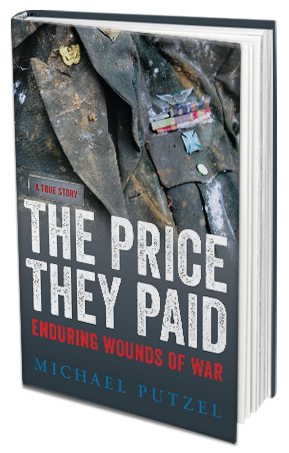

Jim, how can I say anything but thank you for that warm tribute? It was a privilege to work with all of you in the writing of The Price They Paid: Enduring Wounds of War.

With regard to Clyde, himself a great story teller, and his

new high honor/achievement, I say Hear, Hear, well due and deserved.

Jim Kane (21)