Blog

Vietnam vet crosses U.S. to thank the docs who saved him nearly 50 years ago

Posted by Michael Putzel • May 14, 2018

The little scout helicopter sailed in “low and slow” at about one hundred feet off the ground as the pilot and observer in the front seats looked for signs of the enemy. Specialist 5 John Fogle, the crew chief, was scrunched into the little bird’s only other seat in a cramped space that barely had room for him, his M-60 machine gun pointed out the open doorway, and a box of ammunition. His seat faced the door, giving him the widest possible arc to point his weapon—and the maximum exposure to enemy fire.

Artist: Dan Greer

As the helicopter cleared the edge of a canyon, Fogle spotted about a dozen North Vietnamese soldiers directly below, out in the open, and clearly not expecting company. One was hanging up his laundry on a clothes line. At almost the same moment, the enemy soldiers caught sight of the bubble-faced light observation helicopter and grabbed their AK-47 assault rifles. Fogle swung the barrel of his gun down toward them and started to open fire, but one of them got him first.

A bullet tore into the 22-year-old soldier’s right thigh, shattering the femur, the large bone in the upper leg. Blood spurted from the wound and sprayed his uniform. A second shot caught him in the right arm at the elbow.

“I figured I’m dead, so I might as well keep shooting,” Fogle recalled years later. It was hardly worth the effort, trying to shoot the weighty machine gun with his left hand, but he hoped shooting down would make the enemy duck and suppress their firing from below. A Cobra helicopter gunship flown by Captain Frank Sama was covering the “little bird” from above and pushed the nose of his aircraft down to dive on the enemy, but Fogle’s pilot saw what had happened to his crew chief and ordered Sama to cease firing and break away to lead them to a hospital. They didn’t have much time.

With blood still spurting from the femoral artery in his leg and neither of his companions able to reach him, Fogle focused on a bungee cord in front of him that was attached to the aircraft above his head at one end and to his machine gun at the other to hold the weapon up while the gunner aimed and fired. As the helicopter whirled away from the shooting, Fogle pulled off the cord and stretched it tightly around his upper leg to stanch the gusher. It helped slow the erupting stream, but Fogle already was bathed in his own blood. “It was spraying me in the face,” he wrote later. “I couldn’t see anything.”

The bullet had also fractured the tibia bone in his lower leg, a serious wound but minor compared to the ruptured artery, damaged nerve and muscles and compound fracture of the femur.

Sama’s Cobra led the scout as they raced out of the hills toward an American base at Phu Bai, only about ten miles to the east, where the Army had installed the 22nd Surgical Hospital, a row of inflatable quonset huts with wards, four operating rooms and an array of diagnostic equipment and supplies. It even had air conditioning, a rare luxury in the tropics.

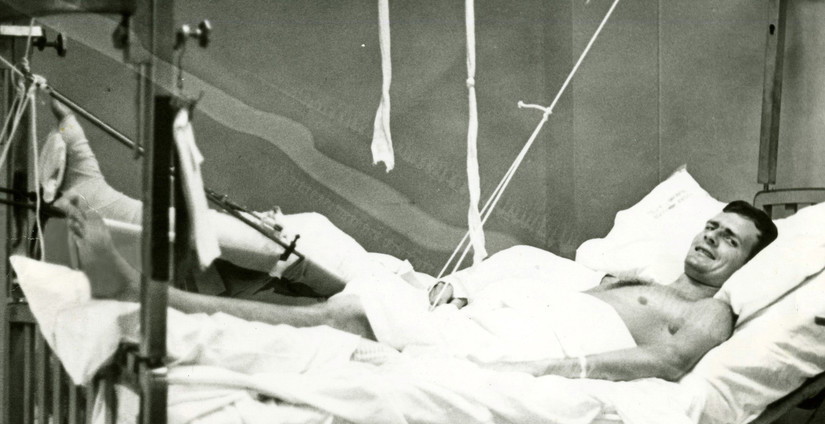

The scout pilot, 1st Lieutenant Alan Szpila, wasn’t familiar with the sprawling military base and told Sama to guide them in to avoid losing critical time hunting for a big red cross painted on a landing pad. Fogle remembers the pain “like a hot poker running through my leg” as the crews and medics pulled him out of the chopper and loaded him on a gurney, then moved him onto a hospital bed inside. The medical staff hovered over him to remove his flight suit and clean the blood off his body. The flight had taken only about ten minutes, but Fogle figured he remained conscious for another half hour before he started to fade, either going into shock or, more likely, after he was given a drug to knock him out. He doesn’t remember going into the OR.

“They saved my life,” he said of the doctors and nurses. “I don’t know how much longer I could have gone.”

The surgeons debrided the wound sites, cleaning away as much of the destroyed tissue as possible and sanitizing the areas to prevent infection. They operated on his upper left leg to remove a three-inch section of vein that they grafted onto the damaged right femoral artery to close the most dangerous wound. His leg was put in a cast, but reconstruction of the bone–or perhaps amputation of the leg—was left to surgeons at a more sophisticated medical facility. The initial operation took two-and-a-half hours, and Fogle was given five pints of blood to replace what he lost. He was kept in the hospital for a couple days to stabilize him, then transferred to the 95th Evacuation Hospital in Da Nang, where he was put aboard a military hospital plane for a five-hour flight to Japan and a short ride in a litter attached to a medevac helicopter that took him to the U.S. military’s 249th General Hospital at Camp Drake.

Four days after he was shot, Fogle underwent more major surgery to put his femur back together and secure it with a metal plate. A wire was inserted to repair the less complicated fracture in his lower leg, and doctors cleaned out the arterial wound some more and removed dead muscle surrounding it. It was just the beginning of a long slog to recovery.

After about a month in Japan, Fogle, a native of Kansas, was flown back to the United States to continue his rehabilitation at Fitzsimmons Army Hospital in Colorado, where a brother and sister lived. He spent sixteen months there, lying in traction when he wasn’t doing physical therapy to strengthen his leg and arm. As he was finally approaching discharge at the end of 1970, a doctor asked him what he intended to do, and Fogle said he expected to find a job repairing aircraft, as he had been trained to do. The doctor told him it would be at least another year before he would be strong enough to crawl around under and climb on airplanes or helicopters. He urged the disabled soldier to go back to school on the G.I. Bill and learn to do work sitting down. He applied to Northrop Institute of Technology, an offshoot of Northrop Aviation, one of the leading defense contractors of the day.

Fogle was accepted a week later, enrolled at the institute in Ingleside, California, and earned his degree in electrical engineering. He worked on helicopters, airplanes and satellites for the rest of his career, retiring in 2011.

When he left that first hospital in Phu Bai, Fogle promised to write to let the medical team know how his recovery went, but the 22nd Surgical Hospital was closed a few months later, and the medical staff scattered to other facilities. Fogle lost touch but never forgot his long struggle and those he credited with saving his life, especially Dr. Mo Levine, one of the surgeons who worked on him in those first hours.

A few months ago, after attending a reunion of his own unit in Vietnam, C Troop, 2nd of the 17th Cavalry, 101st Airborne Division, Fogle determined to track down the people from 22nd Surgical Hospital to learn who they were and thank them if he could. He remembered he had long carried a card that was sent to him by the Vietnam Vascular Registry, a database project begun by an Army doctor who served in Vietnam and wanted to follow patients who had suffered traumatic injuries to major veins and arteries in the war. The registry begun by Dr. Norman Rich at Walter Reed Army Hospital and still maintained by him a half-century later, collected and analyzed the records of more than 10,000 vascular wounds.

When Fogle contacted the registry, he learned his own hospital records were on file. He immediately requested copies and found the names of several of the people who were in the operating room that day on July 25, 1969, including Dr. Monroe Levine, the assisting surgeon, and Terry Caskey, an OR technician who was present during the operation. He also learned the hospital staff from those days was about to hold a reunion of its own in Orlando, Florida, in May. Fogle and his wife Barbara flew to Orlando from their home in Dana Point, California, to meet those who helped save him and others during the war and to tell them how his life had turned out.

Dr. Levine, unfortunately, was ill and unable to attend, but Fogle said he hopes to visit him later at his home in Colorado and thank him in person.

At a gathering of C Troop veterans a few years ago, Fogle learned his superiors recommended him for a medal to recognize his continuing to defend his aircraft and fellow crewmen despite his disabling wounds. The paperwork apparently got lost, and Fogle asked the Army to consider giving him the long-forgotten award. It took two years and a determined effort to gather the required witness testaments and official support, but the Pentagon eventually agreed that he deserved an Air Medal with a V device for valor.

Sama, the Cobra pilot who helped Fogle’s little bird get him to the hospital, said he wished he could have prevented the crew chief from being wounded, “but I’m convinced that John’s actions in returning fire, even though wounded himself, saved the ship from being shot down.” Fogle’s own pilot, Lieutenant Szpila, agreed, noting in a sworn affidavit that the crew chief not only saved his fellow crew members, but the helicopter as well.