Blog

Farewell to a friend

Posted by Michael Putzel • September 30, 2017

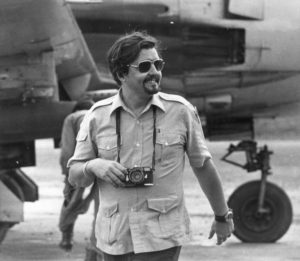

When I stepped off the Pan Am plane that brought me to Vietnam the first time in the fall of 1969, a small crowd of greeters was assembled on the tarmac between the new arrivals from the plane and the obligatory customs and immigration officials waiting for us inside the terminal at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut (now Tan Son Nhat) Airport. There was a war on, but only one person was wearing a helmet. He had on a custom-made civilian “TV shirt” with epaulets and multiple pockets, including one for pens on the left sleeve and another for cigarettes on the right. I was already nervous about my new assignment as a war correspondent and probably took little comfort in hearing the guy with the steel pot on his head call out my name. I headed for him, and he introduced himself as the AP bureau’s news editor, known then as “Dick” Pyle. Pyle shucked the helmet with a smile, saying he had borrowed it from a military policeman because it bore my initials, MP, in large, white capital letters on the front. I’d never been welcomed that way before.

It was the beginning of a friendship and collaboration that endured for nearly a half century. Richard Pyle died at a hospital in Brooklyn on Sept. 28, 2017. He was 83 and suffering from debilitating lung disease.

Richard, as he later insisted he be called because “I always hated being known as a dick,” was as passionate as anyone I have ever known about getting the story right. We didn’t always agree, but I never thought for one moment he had any motive other than to make a story stronger and more accurate. He could also make it read better. His memory for detail was exquisite—and not limited to stories he covered. He knew endless facts about Civil War battles and how they were reported, Amelia Earhart’s last flight and the life and death of Ernie Pyle (to whom he was sometimes compared and for whom he was occasionally mistaken).

The intensity of covering big stories got him ramped up to fever pitch that could explode into rage if the Foreign Desk in New York cut too much detail out of a war roundup or softened a lead he had crafted to a razor’s edge. Pressure excited him and sometimes made him calm when others were losing it.

One of my worst moments was in calling the bureau from a remote Army base over a crackling and uncertain military phone line on Feb. 10, 1971, to report that our beloved colleague and friend Henri Huet had been shot down in Laos with three other news photographers. I asked for Pyle, by then the bureau chief, and shouted my news as loudly and slowly as I could while he typed the words he could discern through the static.

“I had never done anything like it before and have not since,” he wrote decades later in the book Lost Over Laos. “It should have been difficult, writing through tears. But the words rolled out of my typewriter like any other breaking story.”

His fingers failed him three years later on a world-shattering scoop. He had been reassigned to the AP’s Washington bureau and was checking reports that Vice President Spiro Agnew, under investigation for taking cash kickbacks when he was governor of Maryland, had been seen entering a federal courthouse in Baltimore. Pyle called the vice president’s office, where a sobbing secretary told him the vice president had just resigned. Richard immediately informed the assistant bureau chief, Walter Mears, who ordered a halt in filing to the wire to await a bulletin. Pyle turned to his typewriter to slam out the words, but his fingers all hit the keyboard simultaneously and jammed the keys. Without a pause, Mears rolled a piece of paper into his own machine and took Pyle’s dictation: “WASHINGTON (AP) – Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned Wednesday, his secretary said.”

Richard was mostly a hard-news guy and covered wars on several continents, but we spent six months together on a single investigative story. AP’s leadership decided that Senator Edward M. Kennedy was likely to run for president in 1976 and we needed to clear up the many questions surrounding Kennedy’s fatal automobile accident on Chappaquiddick Island off Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., on July 18, 1969. A young woman who had worked for the senator’s murdered brother, Robert Kennedy, drowned in the sinking car as Edward Kennedy escaped. The resulting 10,000-word story, which may still hold the record for length of a single story on the AP wire, concluded that Kennedy’s leaving the scene, ostensibly to report the accident, could not have happened as the senator described it. Richard, however, was never satisfied with getting all those words on the wire because there were still some facts we couldn’t pin down.

He had a great touch writing obituaries, especially but not exclusively of AP colleagues, and had a knack for picking anecdotes that beautifully illustrated the life of his subject. He kept writing them even after his retirement. I told him I hoped he would someday write mine.