Blog

But When Did It Start?

Posted by • April 30, 2015

Today marks the indisputable 40th anniversary of the fall of South Vietnam and, for all to see, the end of the decades-long struggle known in the West as the Vietnam War. In Vietnam, it is called the American War.

The event is being flamboyantly celebrated by the Communist government’s supporters in Hanoi, the nation’s capital, as well as in Ho Chi Minh City, known before and during the war as Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam from 1954 until April 30, 1975.

Quite a few of my long-ago colleagues who covered the war with me in the South are gathering in Ho Chi Minh City this week for a rare reunion, perhaps one of the last, to remember the exciting, sometimes terrifying, days when they were covering the biggest running news story in the world.

The U.S. government’s official commemoration of the war prefers to pretend April 30 is no big deal. The Defense Department instead has chosen to commemorate “the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War,” a conflict in which Americans had been dying for eight years before the date the Pentagon chose to anoint as the war’s beginning.

It is hardly the only misinterpretation of history on the Pentagon’s Vietnam War Commemoration website. What pass for “facts” in the official site’s chronicle of the war are frequently flat statements with no context or attribution and vehemently disputed by others.

My own choice for marking the start of the war, events that actually did occur a half century ago, isn’t even on the Defense Department historian’s list of seven possible starting points, ranging from May 8, 1950, to July 25, 1965. I readily concede that pick is based on my personal recollection of events, supported by later research.

I was in Army basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky, when an American airfield that most of us had never heard of and a nearby headquarters were attacked by North Vietnamese sappers in a surprise assault that killed ten Americans and destroyed a like number of planes and helicopters. The place was Pleiku, a provincial capital in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The coordinated assaults began at 2 a.m. Vietnam time, February 7, 1965.

It was, without question, the worst direct attack Americans had experienced against one of their own bases in Vietnam.

Somebody in our platoon of baby-faced trainees heard about it on the radio, and within hours, the notorious Army rumor mill had us being rushed through an abbreviated training schedule and shipped straight to Vietnam. None of us, with less than two months military experience, realized how ridiculous it was to think the bureaucracy-bound Army could react that fast to anything.

However, from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s vantage point, the attack on Pleiku and another attack 48 hours later that killed 22 Americans in a billet 75 miles away were a clear sign the United States had to respond in force. He took the war to the North with a bombing campaign known as Operation Rolling Thunder, and he ordered units of the 3rd Marine Division to go ashore at Da Nang to protect the U.S. air base there that served as a staging area for the air raids to the north.

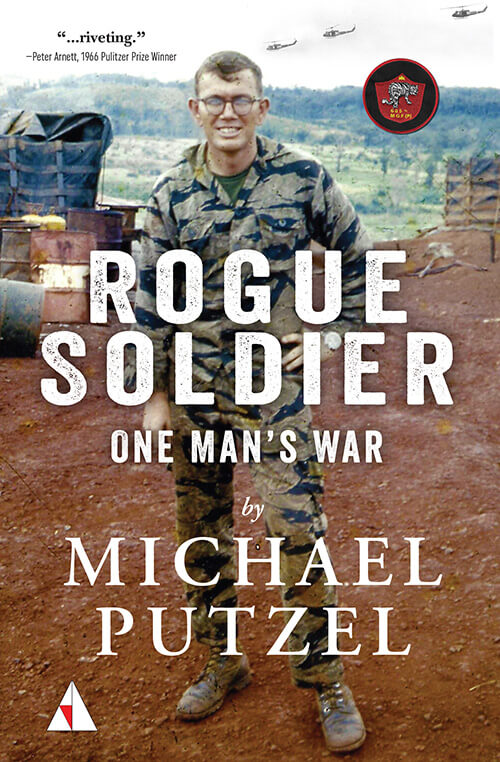

Within months, tens of thousands of U.S. forces were committed to battle on the ground and in the air. But by the time the Army joined the fight in substantial numbers, I was off active duty, in the Reserves and most of the way through my six-year military obligation.

It wasn’t until 1969, when the United States had a half-million men in Vietnam that The Associated Press finally agreed to send me to cover the biggest story in the world.