Blog

Alive Day–the day he almost died

Posted by • April 07, 2016

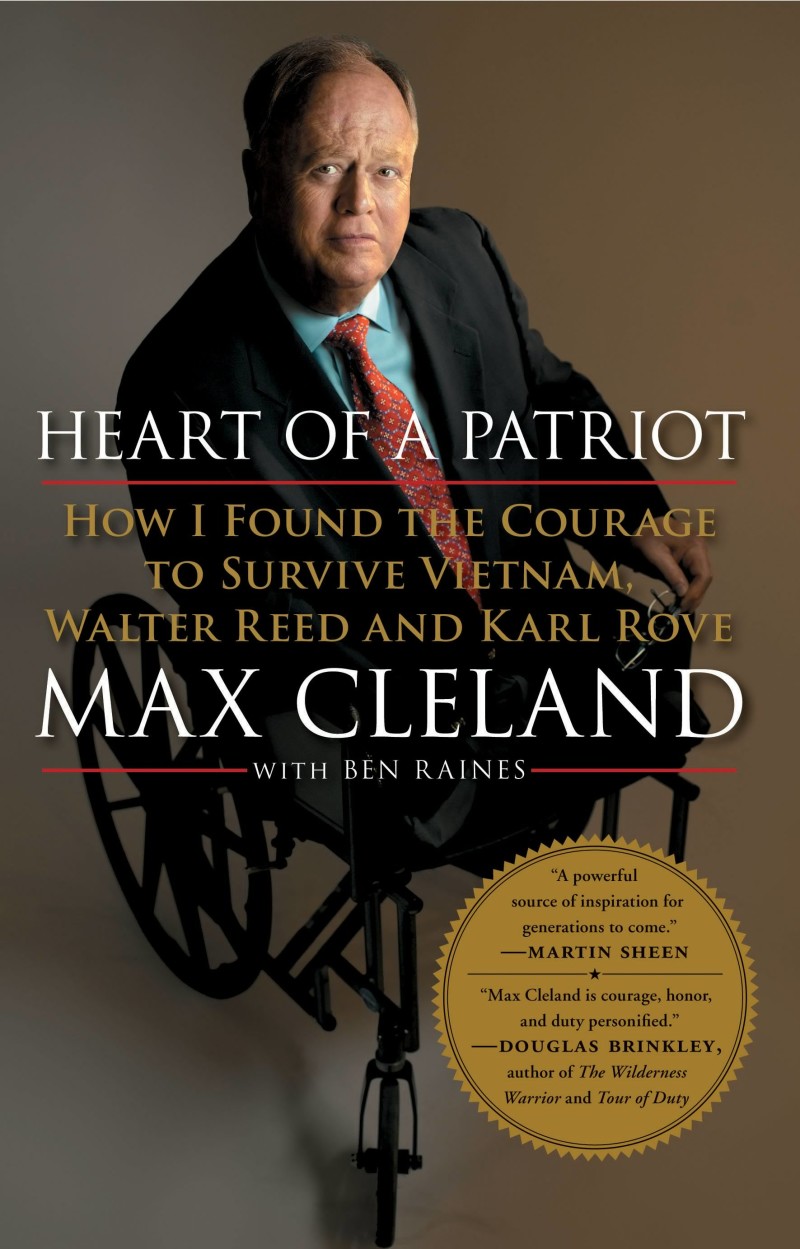

On Friday, April 8, Max Cleland will celebrate the 48th anniversary of the day he got blown up in Vietnam.

“I should be dead,” he told me this week. He is anything but. Cleland has made another astonishing recovery, less dramatic than that day he lost three limbs and 42 pints of blood in Vietnam, but he is back once again, this time from years of severe depression and a bout with long-dormant post traumatic stress disorder.

Cleland was a freshly promoted captain in the Army Signal Corps when the thousands of men and dozens of helicopters of the 1st Air Cavalry Division were ordered to relieve the beleaguered Marines at Khe Sanh, a mountain combat base in the northwest corner of South Vietnam. The Marines had been under siege for 77 days, taken severe casualties and were in danger of being overrun by North Vietnamese regulars massing in the surrounding jungle.

The young Army officer nearing the end of his tour said it was stupid of him to volunteer, but he took a mission to fly onto a hilltop landing zone where he and a couple of soldiers were to install a radio relay station to keep the division’s headquarters in communication with its units in the field. As their helicopter lifted off and flew away, Cleland spotted an American grenade on the ground. He figured it had fallen off his web belt and bent down to pick it up.

The explosive device actually had tumbled from the belt of another soldier, a new guy who hadn’t learned yet to bend or tape his grenades’ pins to prevent them from slipping out of “safety” and arming the explosive inside to go off in a matter of seconds. Boom!

The blast ripped off the captain’s right arm and leg and shredded his other leg as a piece of shrapnel slit his windpipe, rendering him unable to speak. An alert Navy corpsman on a medevac chopper used his belt as a tourniquet to slow the bleeding from one leg, and Cleland was evacuated to an aid station, then to a military surgical hospital at Dong Ha, where a team of doctors labored for hours to save his life. The remains of the left leg had to be amputated, but he kept his left arm.

Cleland eventually got to Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, where he was among many severely wounded combat veterans from Vietnam who endured long and difficult rehabilitation to teach them to live in a world dictated by their disabilities.

Cleland chose to devote himself to public service as a watchdog for veterans’ needs. He was elected to his native Georgia’s state senate before the war was over, and when Jimmy Carter was elected president, he picked Cleland to head what was then a sub-Cabinet Veterans Administration. It was difficult to imagine, in those days before the Americans with Disabilities Act, that a triple amputee could run a major government agency, but Cleland proudly devoted himself to improving the conditions for the thousands and thousands of veterans returning from Vietnam, their lives upended by a year or more and half a world away from anything they had ever known.

A political animal, Cleland ran and was elected to the United States Senate from his native Georgia and served six years before a Republican challenger, Saxby Chands, challenged his patriotism and won his seat.

By his own account, Cleland sank into a deep depression, at least some of which he traces to the Iraq war. He blamed himself for voting to support the war out of fear he would lose his Senate seat in the hyperpatriotic fever that followed 9/11. He returned to Walter Reed and spent three years as an outpatient, struggling with his own demons and helping other veterans battle theirs in regular group therapy sessions.

“ I never saw it coming,” he wrote in The New York Times afterward. “Forty years after I had left the battlefield, my memories of death and wounding were suddenly as fresh and present as they had been in 1968.

“I thought I was past that. I learned that none of us are ever past it. Were it not for the surgeons and nurses at Walter Reed, I never would have survived those first months back from Vietnam. Were it not for the counselors there today, I do not think I would have survived what I’ve come to call my second Vietnam, the one that played out entirely in my mind.”

One of Cleland’s proudest achievements as head of the VA was the opening of the first Veterans Center, a federally supported storefront in Van Nuys, California, designed to be more accessible and less imposing than the sprawling VA hospitals scattered around the country. Today there are 300 such centers—and Cleland is an outpatient at one.

About a year ago, he was diagnosed with a severe heart problem that would require open-heart surgery and considerable risk. Cleland fell back into the debilitating panic he had experienced after his Senate defeat in 2008. He walked into a Veterans Center in Atlanta, joined a group with trained VA counsellors and credits the therapy with helping put him back on course running the American Battle Monuments Commission. When he was admitted to the hospital for the dreaded heart surgery, a pre-operative test showed his problem was not as severe as first thought, and the surgery wasn’t urgent after all.

For victims of PTSD, he told me, “anniversaries are a bitch.” They bring back all the paralyzing memories of awful events that happened long ago. He learned to cope, he said, by adopting the technique of another sufferer, who told his group to celebrate the anniversary as “Alive Day,” the day he didn’t die.

This year, Cleland, 73, is celebrating Alive Day over dinner with Bill Chapman, who lived five doors down from him on Main Street in Lithonia, Georgia, when they were growing up. Chapman became a helicopter pilot in Vietnam, and when he heard what had happened to Cleland, he flew north from his base to see his dreadfully wounded friend in a hospital Quonset hut. Cleland remembers being desperately thirsty after his surgery and loss of blood but restricted to what little water he could squeeze or suck from a water-soaked cotton ball.

Chapman asked him if there was anything he could do, and Cleland asked for a drink of water. His buddy went away and came back a short time later with a cup of Kool-Aid. Not all memories of that terrifying time are bad ones.